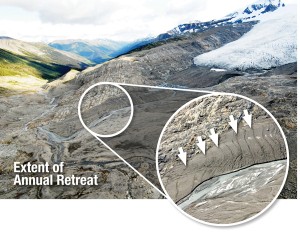

The tip of the Castle Creek glacier near McBride has receded about 750 meters since research began 50 years ago. Castle Creek is unique in North America because it leaves behind rings that show the annual glacial retreat. Above: PhD student Matt Beedle (left) and professor Brian Menounos measure changes in glacier thickness using GPS.

By Laura Keil

Scientists say the past summer was a bad one for BC glaciers – including glaciers in our own backyard.

It was the hottest June on record for many places around the world, including in B.C. where at least 64 temperature records were broken during the heat wave.

UNBC geography professor and glacier researcher Brian Menounos says this year was “an exceptionally strong melt.”

“This was without question one of the highest melt years we’ve seen for that glacier,” he told the Goat, referring to the Castle Creek glacier near McBride.

Over the past decade, the terminus (the tip) of the Castle Creek glacier shrank at a rate of roughly 15m per year. This summer, the rate accelerated to approx. two and a half times that pace.

Menounos says if melting continued at this rate it would meet the extreme end of their melt projections. His joint research announced last spring projects that Western Canadian glaciers would lose up to 70 per cent of their volume by year 2100.

A UNBC article puts it plainly: imagine filling up BC Place Stadium with water. Then empty it. Now repeat the process 8300 times. This would require 22 billion cubic metres of water, the same amount that BC’s 17,000 glaciers are permanently losing each year.

“Glaciers are sensitive indicators of climate, but they are also among western Canada’s most important freshwater resources,” Menounos says.

Water from the glacier does not feed McBride’s drinking water, but its melt portends an uncertain future for many Western Canadians who rely on glacier melt in late summer.

Researchers from Universities in Alberta, BC, Washington State, in addition to scientists from the federal government were part of Menounos’ recent study, which documented recent glacier retreat and the current health of glaciers.

The research team focused their efforts on several glaciers and icefields in BC including Castle Creek Glacier near McBride and glaciers in the Columbia River Basin. At each site, meteorological measurements such as air temperature, wind speed, precipitation, and humidity were taken to better understand the controls of glacier nourishment and melt. The researchers also measured changes in thickness, extent, volume, and movement of hundreds of glaciers throughout the mountain ranges of western Canada. The work required the analysis of thousands of aerial photos, some of which go back 70 years.

During a visit to Castle Creek Glacier, UNBC doctoral student Matt Beedle measured changes in the glacier’s volume through intensive field work. A month earlier, a pole he had stuck into the glacier with only a few millimeters showing at the top was now exposed to nearly his height. Using GPS equipment that can measure his elevation on the glacier within a centimetre, Beedle was able to confirm that the thickness of the glacier at that point had dropped more than 1.5 metres in one month.

But the Castle Creek Glacier is a significant research site for other reasons. As it has been melting, the glacier has left a series of rows of rock and earth (called moraines) that precisely indicate how much the glacier has retreated each year. Similar to tree rings, they extend into the valley 750 metres from the glacier’s current edge, providing a unique geological record of this glacier’s retreat over the past 50 years.

“We’ve never seen moraines like this outside of Iceland,” says Beedle, who has also worked on glaciers in Alaska. “These moraines allow us to see even subtle annual variations in glacial retreat. What a global treasure.”

Surface runoff from retreating glaciers is expected to peak between 2020 and 2040, with substantially reduced flows expected for the remaining half of the 21st century.

BC and Alberta have more than 17,000 individual ice masses, and these glaciers provide cool, plentiful water to many of the region’s headwater streams during late summer when seasonal snowpack has become depleted.

The loss of glaciers has direct implications on aquatic ecosystems, hydroelectric power generation, mining, alpine tourism, and water quality, says Menounos.

“While the wetter Coast and St. Elias Mountains are expected to only lose about half of their glacier volume, the drier interior and Rocky Mountains are projected to lose most of their glaciers, with projected area and volume losses of 90 per cent relative to today.”

When asked what he would say to the Canadian delegation to the UN Climate Change conference in Paris next month, Menounos said he would tell them we have to act now.

He says we still have time to change the course of loss to the larger glaciers if we can stem some of the harm from human-made greenhouse gases.

“It’s our turn to act,” he said.